Stateful Property-Based Testing in Action

Preface

I want to get back into writing, might as well start by re-publishing some of my old internal blogs. This one is particularly public already since I’ve given a talk publicly 1 albeit in a small conference.

The original post is written in April 2018. I’ve also given talks both internally and as a guest speaker at a friend’s company 2. It’s quite a rewarding experience to deliver the “same” talk but to entirely different audiences:

- my colleagues know all about EVE but none about Elixir or PBT

- at friend’s company I have to explain both EVE and Elixir

- finally at the Elixir conference where people know all about Elixir but none about EVE

I spent a lot of effort in both refining the talk in general and adjusting the content according to the audience. I believe I’ve given my best at the time and was pretty satisfied. Even though I didn’t get much feedback or any real follow up - it seems pretty hard to talk about PBT without touching on a lot of project details.

Note that the project that is the subject of this post was only a prototype, it has not been integrated into EVE Online at all and has seen no development for many years now.

The Test Subject

For the last few months, I’ve been working on a project named “LIAR” in my spare time. Which aims to replace and improve the current “attribute modifier” system in Dogma (aka. space combat in EVE). While the main goal is to utilize multi-core & multi-node parallelism, this also provides some opportunities to explore ways to improve the current system, from both technical and gameplay designer’s perspective.

Using the Actor model from Erlang/Elixir, LIAR puts each “Location” into its own Erlang Process (I prefer to simply call it “actor”), multiple actors can run in parallel on different cores, compared to the current Python implementation, which manages all “Locations” in a single OS process, and serially handles update on different locations.

Actors “share data” through message passing. For example, modifiers between locations are created by sending messages. When source value changes, it also sends messages to propagate the change to other locations. Performance should increase as computations on different actors are done in parallel.

TDD and PBT

When talking with our TD before set out to write any code, we also talked about TDD, and I was convinced to try it out with this project. I didn’t do much “unit test” since most basic constructs (Item, Attribute etc…) are just simple struct and access wrapper, the complexity is in where everything interacts together 3.

What I did is more like integration test, where I actually boot the entire stack, setup many things and then assert after some interactions. With top-level APIs defined pretty early on, I find it quite straightforward to do TDD - albeit a lot of duplication for setup. For example, I had a test for “add item modifier should modify the target attribute value” where I add an item modifier within a same location, after I make the “local” version working I can tweak it just a bit to have another test checking “add item modifier between different location should also work” where I now add an item modifier between different locations, it fails to begin with, then I add code to make it pass. The same process continues as I build up other features.

TDD does bring quick iteration cycles and focus on small steps during feature development, I find it very useful when adding features as planned, all current APIs in LIAR are written with TDD. But I also experienced many weaknesses of it, such as duplication of setup code, only testing simple and obvious cases, requires human attention for edge cases etc.

And most importantly, since TDD naturally drives developing the system feature by feature, each test is also focused around a specific feature, which makes me rarely think about interactions with previous features, or even any other feature. For example, I have a specific test for adding item modifier, but that is right after I load items, what if I load and unload and load again? Will everything still work as expected? (Spoiler: no!) Such sequences of operations have near infinite possibilities, so expecting a human to think of all the edge cases that could happen with a random sequence of operations is impossible.

Luckily, stateful Property-Based Testing (PBT) provides tools to help. But before we look at stateful PBT, a quick primer on stateless PBT does no harm.

I wrote a post as well as an internal talk to introduce it more than a year ago. Where I showcased a so-called “stateless property”. To recap, the technique is about to find out a property which always hold true within the problem space as defined in your generators, the tool will automatically explore the problem space and try to find any “counter example” that invalidates the defined property. I started to look at this again as Fred published his work on a new book: PropEr Testing which talks about PBT in detail using the Erlang PropEr library.

As a dumb example, we can write this property (in Elixir using PropCheck):

property "new attribute have correct data" do

forall {id, value} <- {integer(), oneof([integer(), float(), boolean()])} do

attr = Attribute.new(id, value)

assert Attribute.get_value(attr) == Attribute.get_base_value(attr)

assert id == Attribute.get_id(attr)

end

end

Which defines 2 properties when a new Attribute is created:

- its

valueshould be the same asbase_value, since no modifiers are modifying it yet - its

idshould always be what we tell it to be

Here, integer(), float(), boolean() and oneof() are all “generators”, property and forall are constructs provides by the tool to build the test. I explored just using these to explore the problem space for each single function in my previous blog.

Stateful PBT

In any OOP languages such as Python, what we actually concerned about the most are the “running instances” of different classes, since they hold and mutate states. In Elixir/Erlang, an actor serves the same purpose yet in a much cleaner way. Stateful PBT is a way of testing for these, where we assert on the consistency and integrity as the state(s) mutate over time.

In essence, so-called “stateful PBT” extends the basic “stateless PBT”, where we generate a series of command to run, checking results and/or property at each step. To find the expected value to check the result against, the technique we’ll discuss in this post is based on an “abstract state machine” 4. The idea behind this technique is to view the code being tested as a black box, in the test we maintain another state machine, we say it’s “abstract” because it should be a simplified version of how the system actual manages state. With the generated series of command, we run each command against both the abstract state machine and the actual system, and compare results.

Nevertheless, the stateful test looks quite similar to a stateless one:

property "Liar top level APIs" do

forall cmds in commands(__MODULE__) do

# setup

{history, state, result} = run_commands(__MODULE__, cmds)

# teardown / cleanup

result == :ok

# custom output

end

end

Here commands and run_commands are APIs of PropEr to aid writing a stateful PBT case. commands uses a few callbacks defined in the abstract state machine to generate a series of commands, and run_commands uses a few other callbacks to run the commands in both the state machine and actual system, as well as check results.

Example: Fixing a Concurrency Bug

An example is worth a thousand words, so let’s see it in action! Below is the test run that discovered the “unload-load” bug, with most meaningless output omitted.

<$> mix propcheck.clean && mix test test/liar_pbt_test.exs

Excluding tags: [skip: true]

...!

Failed: After 816 test(s).

[{set,{var,1},...]

History: [

...

]

State: %LiarPbtTest{

graph: #Graph<type: directed, vertices: [], edges: []>,

items: %{77 => {Liar.Item<id: 77>, 9}},

locations: '\a\t'

}

Result: {:postcondition,

{:exception, :exit,

...}

Commands: [

...

]

Shrinking ..........(10 time(s))

[{set,{var,1}, ...]

History: [

...

]

State: %LiarPbtTest{

graph: #Graph<type: directed, vertices: [], edges: []>,

items: %{77 => {Liar.Item<id: 77>, 9}},

locations: '\a\t'

}

Result: {:postcondition,

{:exception, :exit,

...}

Commands: [

{:set, {:var, 1}, {:call, Liar, :start_location, [9]}},

{:set, {:var, 2}, {:call, Liar, :load_item, [9, Liar.Item<id: 92>]}},

{:set, {:var, 7}, {:call, Liar, :start_location, [7]}},

{:set, {:var, 14}, {:call, Liar, :load_item, [7, Liar.Item<id: 88>]}},

{:set, {:var, 23},

{:call, Liar, :add_item_modifier, [:dr_add, {92, 1}, {88, 46}]}},

{:set, {:var, 24}, {:call, Liar, :unload_item, [92]}},

{:set, {:var, 25}, {:call, Liar, :unload_item, [88]}},

{:set, {:var, 26}, {:call, Liar, :load_item, [9, Liar.Item<id: 77>]}},

{:set, {:var, 27},

{:call, Liar, :add_item_modifier, [:dr_add, {77, 11}, {77, 9}]}}

]

1) property Liar top level APIs (LiarPbtTest)

test/liar_pbt_test.exs:11

Property Elixir.LiarPbtTest.property Liar top level APIs() failed. Counter-Example is:

[

...

]

code: nil

stacktrace:

(propcheck) lib/properties.ex:115: PropCheck.Properties.handle_check_results/3

test/liar_pbt_test.exs:11: (test)

The following output was logged:

02:36:20.528 [error] GenServer {Liar.Runtime.LocationRegistry, 7} terminating

...

02:36:21.043 [error] GenServer {Liar.Runtime.LocationRegistry, 7} terminating

** (FunctionClauseError) no function clause matching in Liar.Item.get_attribute/2

(liar) lib/liar/item.ex:52: Liar.Item.get_attribute(nil, 46)

(liar) lib/liar/location.ex:366: Liar.Location.reapply_modifiers/2

(liar) lib/liar/location.ex:299: Liar.Location.process_update/2

(liar) lib/liar/runtime/loc_actor.ex:235: anonymous fn/3 in Liar.Runtime.LocActor.handle_cast/2

(elixir) lib/map.ex:734: Map.update!/3

(liar) lib/liar/runtime/loc_actor.ex:232: Liar.Runtime.LocActor.handle_cast/2

(stdlib) gen_server.erl:616: :gen_server.try_dispatch/4

(stdlib) gen_server.erl:686: :gen_server.handle_msg/6

(stdlib) proc_lib.erl:247: :proc_lib.init_p_do_apply/3

Last message: {:"$gen_cast", {:rim_target, {92, 1}, {88, 46}}}

Finished in 8.9 seconds

1 property, 1 failure

Randomized with seed 135556

First, let’s go over several sections in the output:

- Each dot before the

!represents a successful test run - When a failure is discovered, first is the generated commands, but these are from the underlying PBT engine PropEr, so not formatted very well for Elixir, generally ignored because

- We can output the commands along with other useful information with proper Elixir formatting, this gives us the first set of:

- History: the state (of the abstract state machine) at each step before failure

- State: the state (of the abstract state machine) when it fails

- Result: some output regarding the failure, this can be a generic

postconditionmismatch or a stack trace if something crashed during the test - Commands: a better-formatted list of commands

- Generally you don’t need to worry about the original failure case, as next up we see PropEr tries “Shrinking”, in this example it succeeded in reducing the commands sequence 10 times, the final failure case is also printed, we can see it reduces the failure case from 27 commands to only 9, of which are all essential steps to repro the failure

- Following PropEr/PropCheck output is the ExUnit output, the first part is usually not useful, especially in this case since we’ve output commands in the desired format already

- The logged output part becomes useful when the failure comes from an actor crash

- By using

@moduletag capture_log: true, log messages generated while running a test are captured and only if the test fails are they printed to aid with debugging - There are a lot of repeated error logs because commands are executed many times during shrinking, it’s usually enough to just look at the last one

- By using

Now, to figure out what went wrong, we first need to find the direct cause from the error log, then look at the commands sequence to infer the root cause. Here, the first interesting line we notice in the error log is:

(liar) lib/liar/item.ex:52: Liar.Item.get_attribute(nil, 46)

Which indicates we’re trying to get an attribute from a nil aka. non-exist Item. This effectively crashed the actor, which leads us to look at the out-most lines:

02:36:21.043 [error] GenServer {Liar.Runtime.LocationRegistry, 7} terminating

...

Last message: {:"$gen_cast", {:rim_target, {92, 1}, {88, 46}}}

These 2 lines are super useful because the first line tells us which actor crashed, and the last line tells us what is the last message it tries to handle, i.e. what message it failed to handle. rim_target here means “remove item modifier at target location”, since the generated commands have no explicit “remove item modifier” command, this must come from one of the unload_item calls.

Next we need to look at the commands which triggered this failure, notice it’s in the format of {:set, {:var, 1}, {:call, Liar, :start_location, [9]}}. This is the “symbolic call” concept, since at command generation time, there’s no way to know the execution result, so {:var, 1} is a placeholder for “the result of running the 1st command”. This makes it possible to use the result of a command in future commands. Removing these “symbols”, we can simplify the commands to:

1 Liar.start_location(9)

2 Liar.load_item(9, Liar.Item<id: 92>)

3 Liar.start_location(7)

4 Liar.load_item(7, Liar.Item<id: 88>)

5 Liar.add_item_modifier(:dr_add, {92, 1}, {88, 46})

6 Liar.unload_item(92)

7 Liar.unload_item(88)

8 Liar.load_item(9, Liar.Item<id: 77>)

9 Liar.add_item_modifier(:dr_add, {77, 11}, {77, 9})

Notice I separated the commands, the first 5 commands should be pretty solid, also they don’t involve removing item modifiers. Here is a visualization of the state at this point:

The next 2 commands are interesting, when we unload an item, we also need to remove all modifiers related to any attribute on it. Modifiers, represented by Relationships in LIAR, are managed in a directed graph, for modifiers between attributes within the same location, we simply remove it from the graph. But for modifiers across different locations, we need to send a message between the 2 actors managing those locations. And this is when concurrency strikes.

It is better explained with a sequence diagram:

Note unload_item is just a message passed from the caller (test case) to different actors (LocActor), and all these messages are async/non-blocking casts. What happens here is on Location 7, it first received the message to unload item 88, but then also the RIM message from unloading item 92 on Location 9 - because it has a modifier on item 88. Since the item is already removed, we get a nil item and trying to access attributes on it resulted in the crash.

Knowing the root cause we can fix it in various ways, here I decided to re-evaluate modifiers only if the item is still loaded on the location.

@spec process_update(t, ia) :: {t, cast_messages}

- def process_update(location, target) do

- location

- |> reapply_modifiers(target)

- |> propagate_attribute_change(target)

+ def process_update(location, {item_id, _} = target) do

+ if Map.has_key?(location.items, item_id) do

+ location

+ |> reapply_modifiers(target)

+ |> propagate_attribute_change(target)

+ else

+ {location, []}

+ end

end

After the fix we simply run the PBT again, PropCheck not only detects a failure and shrink it to only the necessary steps to reproduce it, it also saves this counter example, allowing us to check the fix with the same input:

<$> mix test test/liar_pbt_test.exs

Compiling 3 files (.ex)

Excluding tags: [skip: true]

OK: The input passed the test.

.

Finished in 0.1 seconds

1 property, 0 failures

Randomized with seed 667925

Here it only checked the property against the saved counter example (only 1 dot), and it indeed resolved the problem!

On success, PropCheck will clean up the counter example, so on next run it backs to normal commands generation again:

<$> mix test test/liar_pbt_test.exs

Excluding tags: [skip: true]

...

OK: Passed 5000 test(s).

39% {'Elixir.Liar',add_item_modifier,3}

22% {'Elixir.Liar',get_value,1}

20% {'Elixir.Liar',load_item,2}

11% {'Elixir.Liar',start_location,1}

4% {'Elixir.Liar',get_items,1}

2% {'Elixir.Liar',unload_item,1}

.

Finished in 76.2 seconds

1 property, 0 failures

Randomized with seed 212784

5000 sequences of commands and no error!

Writing a Stateful PBT

As the example shows, stateful PBT is a powerful approach to discover what might go wrong when putting the system to real-world use, I would never have thought about testing for when unloading items on different locations would cause any issue, let alone various other combinations of commands that reveal interesting bugs. But it’s not only powerful, the test case is way more concise and even fun to compose. Here is a LoC comparison at the time of writing:

| Component | Files | Blank | Comment | Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lib/ (source code) | 12 | 238 | 185 | 927 |

| “integration” test | 1 | 80 | 1 | 351 |

| stateful PBT | 1 | 53 | 2 | 177 |

When I look closer at the test code, not only almost 40% of the 351 lines of “integrations” test are used just to set up each test case, there are often only trivial steps involved, I’d never really test how all features work together as that would likely make a test case hard to write and maintain. Yet in the stateful PBT, using only half the amount of code - which even includes an abstract state machine - I’m able to discover a lot more edge cases. The ratio of source code to test and the range of problems it can reveal is impressive to say the least.

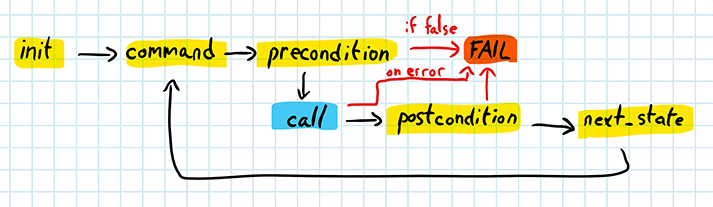

So let’s look at how to write one such test. As mentioned above, stateful PBT is based on basic stateless PBT, with a few callbacks to work with the abstract state machine. The abstract state machine evolves as well as the actual system in a manner like this: 5

With this in mind, here are the required callbacks and examples from my current PBT:

initial_state is used to set up the initial state:

def initial_state do

%__MODULE__{

locations: [],

graph: Graph.new(),

items: %{}

}

end

command is used to generate the next command, according to the current state:

def command(state) do

frequency([

{10, {:call, Liar, :start_location, [gen_new_lid(state)]}},

{50, {:call, Liar, :load_item, [gen_loaded_lid(state), gen_new_item(state)]}},

{10, {:call, Liar, :unload_item, [gen_loaded_item_id(state)]}},

{20, {:call, Liar, :get_items, [gen_loaded_lid(state)]}},

{100, {:call, Liar, :get_value, [gen_loaded_ia(state)]}},

{200,

{:call, Liar, :add_item_modifier, [gen_mod(), gen_loaded_ia(state), gen_loaded_ia(state)]}}

])

end

frequency() is used here to control how frequent to generate each command, proportioned to the first number, here my focus is on adding item modifiers.

Next, precondition is used to validate a generated command:

def precondition(state, {:call, Liar, :unload_item, [item_id]}),

do: Enum.member?(loaded_item_ids(state), item_id)

Which means only unloading a loaded item makes sense.

If the command is valid, next_state mutates the abstract state machine:

def next_state(state, _, {:call, Liar, :add_item_modifier, [mod, source, target]}) do

update_in(state.graph, fn g ->

Graph.add_edge(g, source, target, label: mod)

end)

end

Finally, in postcondition we check whether the result is as expected:

def postcondition(state, {:call, Liar, :get_value, [ia]}, result) do

assert calculate_value(state, ia) == result

end

With these callbacks defined, PropCheck/PropEr can do the heavy lifting of finding counter examples.

The concept is simple when distilled, yet there are quite a few intricate details that requires experience and more or less trial and error. I have a few tips to share after spending a lot of time refactoring and understanding these components of a stateful PBT:

- Basic generators can be used to generate arguments for commands, but you should limit the scope of those, since the focus should be on random operations not random input data

- I defined

@max_locations,@max_items

- I defined

- Both

commandandpreconditionare used to guarantee valid commands sequencecommandshould be used to limit (filter) commands based on the current state, this is needed because:- Ensure generator works (e.g.

elements([])will raise exception) - Fine tune command generation according to PBT’s state, increase the success rate of command generation (it makes no sense to “unload item” when no items are loaded in the first place)

- Ensure generator works (e.g.

preconditionshould validate arguments, this is essential for correct shrinking behaviour- Shrinking just delete commands from generated failure case, and only use

preconditionto validate command sequence - Shrinking does not use

commandat all! For example, when the “load item” command for an item is deleted during shrinking,preconditionshould fail any future action on that item, otherwise the shrunken command sequence will represent a drastically different error.

- Shrinking just delete commands from generated failure case, and only use

- DRY with helper functions to list valid things, and wrap generators

- Use

commandto describe “prerequisite”, andpreconditionfor “validation”

- It’s important to NOT repeat the same application logic in

next_state - When changing the PBT itself, use

mix propcheck.cleanto clean up counter example from old test - you’ll need to do a lot of these to develop a solid stateful PBT

For LIAR specifically, an interesting usage of postcondition is to simulate “consistency guarantee”, similar things are done in “integration” test with wait_for_cast. Since different Locations use non-blocking cast to communicate, modifiers across different locations need to wait until all those messages are handled to be “globally correct”. So in the postcondition for commands that might trigger message passing, I wait for some synchronous/blocking calls from all locations, simulating a wait and only assert on “eventual consistency”.

This is actually the reason why command 8 and 9 still exist after shrinking, even though Location 7 has already crashed. I only do such “wait” on all locations that are supposed to be alive when adding an item modifier (step 9). And step 8 is required for 9 - it doesn’t make sense to create modifiers without items.

This shows the power of shrinking, the result contains just enough steps to both produce the failure and observe the failure.

Final Thoughts

Fred has a summary on when best to apply stateful PBT:

Stateful property tests are particularly useful when “what the code should do”—what the user perceives—is simple, but “how the code does it”—how it is implemented—is complex.

One thing I didn’t go into detail in the last section is how I’m checking the result, I thought about it quite a lot, but the final result is surprisingly simple. The code to calculate the desired value from PBT’s abstract state machine is just:

defp calculate_value(state, {item_id, attr_id} = ia) do

{item, _} = state.items[item_id]

base_value = item |> Item.get_attribute(attr_id) |> Attribute.get_base_value()

state.graph

|> Graph.in_edges(ia)

|> Enum.map(fn e ->

{e.label, calculate_value(state, e.v1)}

end)

|> TestModifiers.evaluate(base_value)

end

The interesting part is that this function is doing a “backward” calculation, or more accurately described as “recursive”. While LIAR is doing the calculation in a “forward” style, what effectively determines the value of an attribute should always be its base value and all the modifiers applying to it, however we can’t afford to re-calculate this value every time it’s asked, so what LIAR does is calculate once and store the result, in a sense this can be considered as “caching”.

This leads to another general situation where stateful PBT can be applied: when the actual system is doing forward calculation (and caching), we can apply a backward (recursive) calculation in PBT.

-

The video is here but seems to be missing a section, also pardon my Chinglish xD ↩

-

WuXi NextCode in Iceland, which seems to have rebranded since, my friends there also left ↩

-

which is originally all in

Locationbut later I separated to a purely functional partLocationand a runtime concerning partLocActor. Mostly inspired by this blog ↩ -

Sometimes the “abstract state machine” is also referred to as the “model”, since stateful PBT can be considered as a non-formal variation on model checking ↩

-

credit: PropEr Testing ↩